Interpeted Languages

Merhaba!

That’s “Hello!” in Turkish. Foreshadowing.

What is a Programming Lanugage?

A programming language is a way to represent instructions for hardware, typically a CPU, to execute. This representation may be very high-level, like Python, or it may be very low-level, like assembly (e.g., x86). In fact, assembly is the lowest you can go without writing in pure hexadecimal/binary, since all assembly statements have a one-to-one translation to binary, and are fed directly to the CPU.

Colloquially, a programming language is not just some set of instructions for the CPU to arbitrarily execute. It is a formal, high-level abstraction of all of the nitty-gritty details of hardware. This abstraction enables us to write high-quality safe and understandable code. It’s pretty straightforward to imagine up a new programming language, but how do we go from high-level to low-level?

Compiling

Compiling is the process of translating a high-level language to a machine-executable binary file.

Compiler

Compilers are programs that compile a given language. They must trace through the program, understand links between functions, store global variables, reduce complex class logic to their barest forms, and so on. Compilers often have a set of known optimizations for certain code patterns, and so you can have wildly different performance in the executables generated by two compilers for the same language. An interesting tidbit here is that most compilers are written in the language they are supposed to compile, like Ouroboros1.

Compiled Language

Compiled languages, such as C, C++, and Java, form the base of nearly all modern programming. There are, of course, exceptions, but any web application, software, game, whatever, all roads lead to compiled languages. That must mean all modern programming languages are compiled, right? No.

Interpreting

Interpreting is the process of executing a high-level language with another high-level language.

Interpreter

Interpreters, which are the focus of this article, work very, very differently than compilers. They do not translate one language to another2. Given a language A, and a new interpreted language B, the interpreter, written in language A, will build an internal representation of the code written in language B, and will be able to execute it statement-by-statement. The interpreter’s language needn’t be compiled, although a chain of interpreted languages will seriously slow down execution. An interpreter is both the entire interpretatation program and the final execution phase of the program. More on that later.

Interpreted Language

An interpreted language, such as Python, must have an interpreter written in another language. For Python, that language is C. Code written in Python is scanned, parsed, resolved, and then run in C, again, statement-by-statement. Python, and all interpreted languages, are therefore almost pseudo-languages. It’s like hearing French and having to translate it into English in your head before you understand it.

Typed Languages

A language being typed is not at all related to whether it is compiled or interpreted. Certainly, if a language is compiled, it should be typed, but it is not strictly required. A typed language is not a language that is typed on a keyboard, it is a language that enforces types to variables. For example, if I define a variable to be an integer in a typed language, it can never not be an integer when assigned a new value.

int a = 5;

a = 10; // fine

a = -234; // fine

a = 1.23; // bad!

a = "hello" // bad!In an untyped language, the type of a variable is free to change whenever it takes on a new value.

a = 10 # fine

a = 2 # fine

a = "Hello!" # fine

a = [1, 2, 3, 4] # fineTyped languages, when done correctly, are typically safer, less error-prone, and easier to debug. However, introducing typing to a language can also introduce errors, such as inconsistencies between how the code is treated when it runs versus when a typing pass is done.

float a = 1.5; // normal behvaior, everything works fine

float b = 1; // okay in the typer, but interpreter freaks outIn the example above, the typer may not see a problem with a decimal typed variable being assigned an integer value, but when the code is run, the interpreter may not know how to do that. Concrete documentation is important to maintain consistency across the interpreter and the typer (see my next article).

Structure of an Interpreter

An interpreter has several internal components, all of which execute in sequence. It is possible to encounter errors at any level of the interpretation process. I will present the components in order.

Scanner

We begin with the raw string of the source code file. The scanner will take this string and split it into Tokens, which are known characters, keywords, or patterns. For example, while would be a token, (, too, as well as "hello", {, :, if, and so on. Our scanner sequentially processes all of the characters in the source file, matching tokens with patterns, until it covers the entire file.

If the scanner is in the process of matching a pattern, and encounters an unexpected character, it may throw an error. For example, if the scanner never sees the other quote in a string (e.g., "hello [...] [END OF FILE]), it will throw an error. Additionally, if the scanner encounters an unknown character (e.g., @), it will throw an error.

If the scanner sees the file print("Hello World!"), it would generate the tokens print, (, "Hello World!", ). Tokens also should store the type of the token (print: identifier, (: open bracket, "Hello World!": string, ): closing bracket) and other important metadata, such as the line number and index of the token.

Once the scanner is finished generating the ordered list of tokens, it passes them to the Parser.

Parser

As the characters are to the scanner, the tokens are to the parser. The parser also looks for patterns, but instead of looking at individual characters, it looks at entire tokens. The goal of the parser is to capture the “abstract expressions” that are present in the tokens. In the print("Hello, World!") example above, the abstract expression is a call expression, as we’re calling the print function.

Unlike the scanner, however, the parser does not simply generate an ordered list of these abstract expressions. Instead, it generates something called an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST).

Grammar Syntax Trees

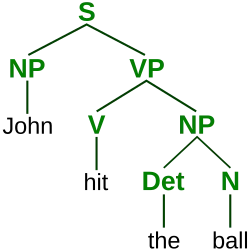

If you’ve studied linguistics or natural language processing, you should know what a grammar syntax tree (parse tree) is. Given some grammar (a set of formal rules dictating how the language can be formulated), you can construct a syntax tree for a valid sentence. An example of a grammar syntax tree is shown below

As shown in the image, our grammar contains at least the rules:

- a Sentence (S) can contain a Noun Phrase (NP) followed by a Verb Phrase (VP)

- S → NP + VP

- a NP can contain a terminal noun (e.g., John)

- NP → terminal noun

- a NP can contain a Determiner (Det) and Noun (N)

- NP → Det + N

- a VP can contain a Verb (V) and a NP

- VP → V + NP

- a V can contain a terminal verb (e.g., hit)

- V → terminal verb

- a Det can contain a terminal determiner (e.g., the)

- Det → terminal determiner

- a N can contain a terminal noun (e.g., ball)

- N → terminal noun

This grammar can be simplified to:

S → NP + VP

NP → Det + N | terminal noun

VP → V + NP | terminal verb

V → terminal verb

Det → terminal determiner

N → terminal nounA terminal is an actual word (e.g., John). In our simplification, a | represents a disjunction (this or that). Of course, the English language has many, many more rules than the above set. If we rigorously define all of these rules, we can theoretically create a grammar syntax tree for any valid English sentence. There are often many possible trees for a single sentence in English, which introduces uncertainty and ambiguity into parsing sentences into grammar trees3, something we would like to avoid when parsing code.

Abstract Syntax Trees

So, what have we learnt from grammar syntax trees? We’ve learnt that it is possible to go from a flat set of tokens to a very much non-flat tree. We’ve also learnt that our grammar rules need to be defined well enough that it should be impossible to get two valid syntax trees for a single list of tokens to avoid ambiguity in our language. We’ve also seen that it’s possible to parse tokens into a tree, but how do we actually do it?

There are several methods to parse tokens into an AST, but the one I learnt is Recursive Descent Parsing. We start at the highest possible “level” of our tree (which would be S in the above grammar syntax tree example), and, token by token, we apply whatever rule we can (called greedy matching). Note that this is why avoiding rule ambiguity is important, since we match rules greedily, we don’t want to encounter two valid rules. We apply rules until we reach the abstract syntax version of a terminal, called a primary. Often, these are limited to literals, like numbers, strings, boolean values (true/false), identifiers (like variable and function names), and grouped expressions.

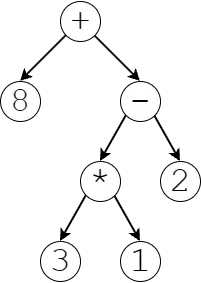

Below is an example of a simple AST representing 8 + ((3 * 1) - 2). Here, operations like addition and multiplication are our “rules”, and numbers are our terminals.

An important note about ASTs is that the rules themselves carry meaning beyond just being a rule. For example, our addition rule carries the meaning of being an addition.

Statements and Expressions

Programming languages, to start, have statement rules and expression rules, which generate statements and expressions, respectively. Everything that is below a statement rule is part of that statement in the AST, and everything below an expression rule is part of that expression expression. You absolutely can have expressions within expressions, statements within statements, and so on, with an important exception.

The main difference between a statement and an expression is hierarchy. Statements always contain expressions or other statements, but expressions never contain statements, ever. Another important difference is that statements do something, whereas expressions give you a value.

For example, an expression could be an addition, a logical expression (this or that), a negation (-a), a number, a string, or the use of a variable. However, a statement would be something like an if statement: if ([expression]) [statement] else [statement]. Here, we evaluate the condition’s expression, which should give us a true or false (boolean) value, and then the if statement does something by deciding which statement to execute. break, continue and return are also all statements, as they have some functionality within the code that does not provide a value4.

Other Rules

There are several other rules, like the top-most program rule, which is similar to our S rule above. There are also declaration rules, which fit in loosely between the program rule and the statement rules in the hierarchy. Typically declarations contain statements and not the other way around, but it is possible. For example, consider a block statement: { declaration* }. Since a block is like another “mini program” (think function definitions), you need to be able to go up the chain a little bit.

Declarations are important as they allow for the declaration of variables, functions and classes (e.g., var x = 5).

So, the hierarchy of rules is generally as follows:

program rule > declaration rules > statement rules > expression rules > primary rulesPrecedence

First, the reason why we have a herarchy of rules that contain each other is because of rule precedence. Rule precedence dictates what rules should have precedence (occur before) over other rules. In recursive descent, each rule is formulated so that it can contain the rule below it, creating a linear chain of rules. The lower a rule is on our chain is, the higher the precedence of that rule is.

Let’s illustrate this with an example. Below is the rule for addition/subtraction followed by division/multiplication:

expression → assignment

...

term → factor ( ( "-" | "+" ) factor)*

factor → unary ( ( "/" | "*" ) unary)*

...

primary → NUMBER | STRING | ...note: any rules higher than expressions have not been included for simplicity

Here, our term rule contains at least a factor, and optionally a + or - sign with another factor. If we didn’t have a + or - sign, that’s fine, since it’s optional. Note that a | indicates “or”, and is equivalent to writing out every rule individually (e.g., primary → NUMBER, primary → STRING, and so on). Notice that the factor in the term rule is on the left hand side, so we evaluate it first in our descent.

Now, a quirk particular to recursive descent parsing is that we always evaluate the smallest amount of a rule as possible. Due to this quirk combined with the fact that the left-hand-side of a rule always contains the rule below it, a token will fall through every rule until it gets to a primary rule, which is our lowest rule type (in recursive terms, it’s our base case).

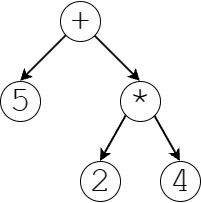

Let’s say that we have the expression 5 + 2 * 4.

- We will start parsing with the first token,

5, which will fall through all of our rules until it reaches theprimaryrule as aNUMBER.- current parsed equation: (5)

- Then, we will crawl back up the chain of rules until our next token,

+, matches a rule. In our case, it would match thetermrule.- current parsed equation: (5) + _

- Since we cannot progress without parsing another token, we parse our

2, matching the secondfactorwithin thetermrule. The2token again falls down the chain of rules until it reaches theprimaryrule as aNUMBER.- current: (5) + (2)

- Then, we go back up the chain until our next token,

*, matches a rule. It matches with thefactorrule.- current: (5) + (2 * _)

- We now parse

4, go down the chain until it reachesprimary, and then go back up. There are no more tokens, so we are done- current: (5) + (2 * 4)

Through processing our rules, we have processed 2 * 4 together, meaning it occurs before it is added to the 5. We have adhered to multiplication before addition through the use of rule precedence. The final syntax tree for this equation is shown below.

Recursive Descent Parsing (or, Putting It All Together)

You start with a list of tokens from the scanner (remember that? phew, that seems like ages ago!). You go through the tokens, token by token, falling through our chain of rules until you reach the primary rule. You then crawl back upward with your next token to check for any matches. Upon the first match, you continue with that rule until you need to either fall through again or crawl up with the finished product of the rule. This “crawling back up” means that lower rules have higher precedence. If you’re familiar with programming, you should be aware that this process is recursion manifest.

We define every possible rule for declaring things (declaring variables, functions), statements (for loops, if statements, …), expressions (addition, etc.), allowing us to parse any valid program written in our language.

Given a program written in our language, we create an abstract syntax tree from the scanner’s scanned tokens that dictates order of execution and logical structure of our program. We never actually compute the values contained by the tree (for example, we don’t compute 5 + (2 * 4))), we just store their execution order and associated metadata.

The parser’s job is complete. It hands over the AST to the next phases.

Resolver

This is either the last step before being able to run the code, or the second-to-last, depending on whether you want your language to be typed. So far, all of our phases have generated something new and passed it to the next phase. The scanner took in the raw file and generated tokens. The parser took in the tokens and generated an AST. The resolver does not transform the AST, instead it provides crucial information to the interpreter on variable scoping information. The AST is actually the final product, used deeply by every following phase, including the final interpreter phase.

Variable Scoping Issues

If you’re not aware, you can define variables in deeper scopes that exist also in outer scopes. Consider the following simple example:

int a = 5;

void printA() {

string a = 12;

print(a);

}In the above example, we are allowed to re-define a within the scope of a function.

When our interpreter runs code, one would naively think that when a variable is accessed, it could search scopes for the nearest variable with the same name, and use that value. However, consider the following example:

int a = 5;

void printA() {

print(a);

}

void printAWrapper() {

int a = 12;

printA();

}Here, our printA() function is clearly supposed to print the value of the global variable a. However, if we naively tried it find it in the closest scope, we would run into our int a = 12 local definition of a. We therefore need a way to know what scope, or how many scopes out, a variable access is intended to be accessed from. This is the main job of the resolver, and it only needs to be run once.

Resolving Variable Scopes

The resolver will go through our list of declarations (which, again, can contain and typically are just a rule that wraps statements), and checks the scoping of the variable at each one. In the above example, it would first register a in the global scope, then register the function printA in the global scope, then register that the a in print(a) refers to the global a. It will pass this information to the interpreter, who now knows to look in the global scope for a, instead of using the locally defined a in the printAWrapper.

Resolver’s Secondary Uses

The resolver can also be used as a sort of heuristic checker, since it is applied to the final AST. For example, it can be used to check whether all variables defined in a scope are used, or enforce that break statements are not used outside of a loop, and so on. These static checks avoid annoying errors when running the code, and allow us to the show the user their errors directly in their editor.

Typer

Warning: This is optional and can be challenging to implement. Deep testing is important to maintain consistency across the typer and the interpreter. The typer does nothing but scan for errors. It is the only phase that truly contributes nothing but verification.

Typing a language changes it slightly, as it requires all variable declarations to have a type and all function declarations to have a return type. See the changes between Python and C# below.

a = 15

def IsNegative(value):

if value < 0:

return True

else:

return False

print(IsNegative(a))int a = 15;

bool IsNegative(int value) {

if (value < 0) {

return true;

}

else {

return false;

}

}

print(IsNegative(a))As you can see above, even the parameter declarations inside functions must be typed. Additionally, simply adding types into our grammar pattern-matching does not solve the issue of typing. Every time a value is used, we must ensure that the type of the value is consistent with its use. Consider the following example:

int a = 15;

bool b = true;

print(a + b);Here, our typer needs to recognize that a + b is an invalid operation because the type of the value of b, bool, cannot be added to the type of the value of a, which is int. This is a good demonstration of how useful typing can be. In Python, this addition would not be flagged as a problem until you run the code, at which point the program will crash and Python will stand shyly with its knees angled together and fingers pointing at each other, apologizing profusely. Any typed language would scoff at such a predictable error.

Recursive Typing

Recursion, recursion, recursion. I have been writing for hours. My keyboard is whimpering. I persevere.

The method I use to evaluate types is a recursive one. Really, types can come from three places:

- Literals, such as numbers (

intordouble), strings (string), and so on. - Variables, whose type should be defined when they are declared.

- The value returned from a function, which should be stated when the function is declared.

So, the recursive method I propose is to evaluate the type of expressions recursively, while also enforcing typing. We must start at the top of the tree (at the program rule), but recall that only expressions give us a value, and only values have types. We may still need to check that the expressions contained in statements have the correct type for the statement in question. For example, in an if statement, we need to ensure that the condition expression is a bool or bool-compatible.

For example, let’s say we’re somewhere down in the depths of recursion at the expression expression + 5. expression is evaluated, its type is found, and if it matches the type of 5, which is int, the typer is happy. The typer will then recognize that the type of this addition expression is int, and then pass it back up the chain of recursion. If a problem is ever encountered, it is flagged as an error and presented to the user.

Dealing with Errors

You do not want to stop typing a program when one error is encountered, as the user will need to play whack a mole whenever they fix one problem and the next one is revealed. Instead, we must handle errors gracefully and continue on without problems. This is straightforward in most cases. For example, if we have a logical expression, we know that the output should be a bool no matter what, even if the expressions being compared are not booleans.

However, error handling gets more complicated when we consider cases like the user writing a type that does not exist for a variable. For example, if the user declares a variable as itn x = 5 [sic], what do we do when x is used later on? Preferably, we wouldn’t like it to cause a slew of errors everywhere just because of a single mistake. To solve this, we can introduce a special ignore type, used only by the typer. Whenever an expression is evaluated and a typing error occurs such that the output type cannot be determined, the ignore type is used. Whenever an expression is evaluated for its type, if any of its contained expressions are of the ignore type, the ignore type is propagated up the recursion chain, and no typing error identification is attempted. In our typo’d variable assignment, we can set the type of the variable to ignore right away, so that any expressions it is accessed in will not raise any errors. Thus, only the original typo ever raises an error.

Interpreter

We’ve made it. This is it. The interpreter has the easiest job of all the phases. Parsing has given us the ability to tell variable and function scope. Typing made sure the user isn’t an idiot. Now, we just need to execute it.

Recall that in our AST, the program contains many declarations. The interpreter executes these declarations one at a time, recursively, similarly to how we checked for types. Instead of recursively checking types, though, we recursively calculate values. For the expression expression + 5, expression is evaluated to find its value, then that value is added with 5, and passed up the recursion chain. These values may be used in statements/declarations, and so on.

Native Functions and Values

However, we currently can’t really do anything with these values. We need native functions, which are relatively straightforward to implement, to interact with systems outside the language itself. These native functions can include print, clock, save, load, which are direct interactions with the environment.

They may also include utility functions, such as abs, log, and so on. Additionally, we can introduce native values (constants), such as PI, E, and so on.

Wrapping Things Up

I hope this was at least entertaining, and hopefully you learnt something if you got this far. If you have any questions, feel free to ask me using my contact on the about page! For an implementation guide of a basic (untyped) interpreted language, I found Robert Nystrom’s book on Crafting Interpreters to be phenomenal.

See you soon.

Footnotes

-

What came first, the chicken or the egg? The mother. ↩

-

There’s actually a whole field of study about this, where grammar rules are assigned probabilities in order to calculate the probability of a given grammar syntax tree. ↩

-

You may think that

returnshould be an expression, butreturn xdoes not actually give you a value. You cannot use it on the right hand side of an assignment, for example:y = return xmakes no sense. However, an addition would be an expression, because it gives you something:z = x + y. ↩